The Archibald mill is located on the banks of the Cannon River in Dundas. Brothers John S. and Edward T. Archibald came to Hastings in 1856 from Ontario, Canada. John worked at the Ramsey Mill for a short time, while Edward operated a real estate business. After witnessing the success of the Ramsey Mill, the brothers decided to strike out on their own and operate their own mill.

John and Edward found the perfect spot with enough water power to operate their mill along the eastern bank of the Cannon River in Rice County. They purchased the water power rights and 1,100 acres of land in 1857. The town of Dundas–named after their hometown in Ontario–was established the same year.

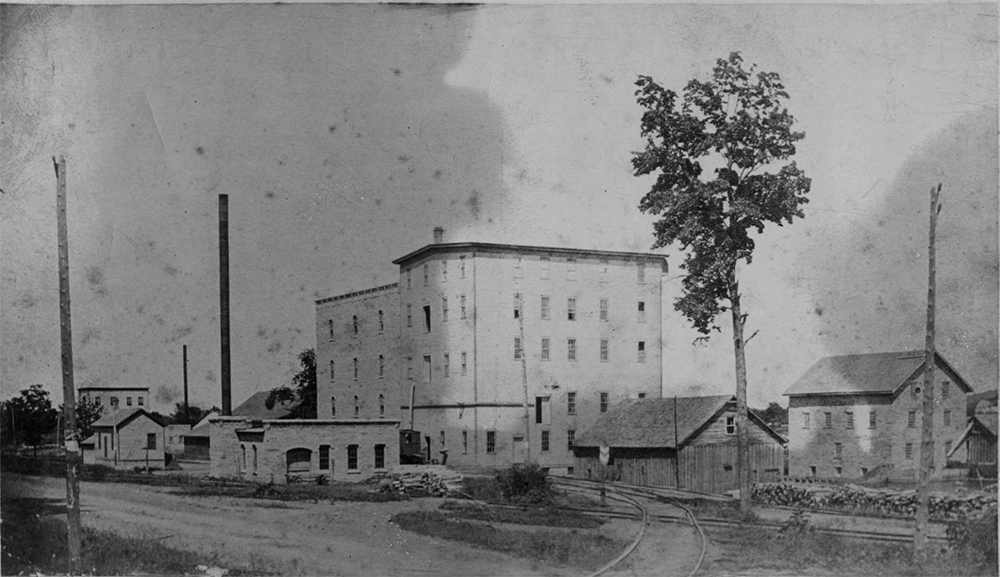

The arrival of Archibald cousin, George, kicked planning and construction at the site into high gear. A stone dam with an eight-foot fall was built to harness the river’s power to operate the mill. Next, the mill was built. It was three and one-half stories and constructed of locally-quarried limestone and finished with black walnut and butternut lumber. Inside, four grindstones made of Ohio quartz did the bulk of the work. Several shakedown sifters with slides were arranged so customers could mix their own flour. The mill operated six days a week leaving the mill open on Sundays for church services to be held there prior to the construction of the Church of the Holy Cross.

High water levels on the river in the early 1860s turned the land surrounding the mill into an island with a second channel created to the east. Then a late-fall storm in 1866 washed out the stone dam. The following year, two similar dams were constructed to replace it. Why two dams? Because plans were quietly being hatched by the Archibalds to build a second mill on the western bank of the river–almost directly across from the first mill.

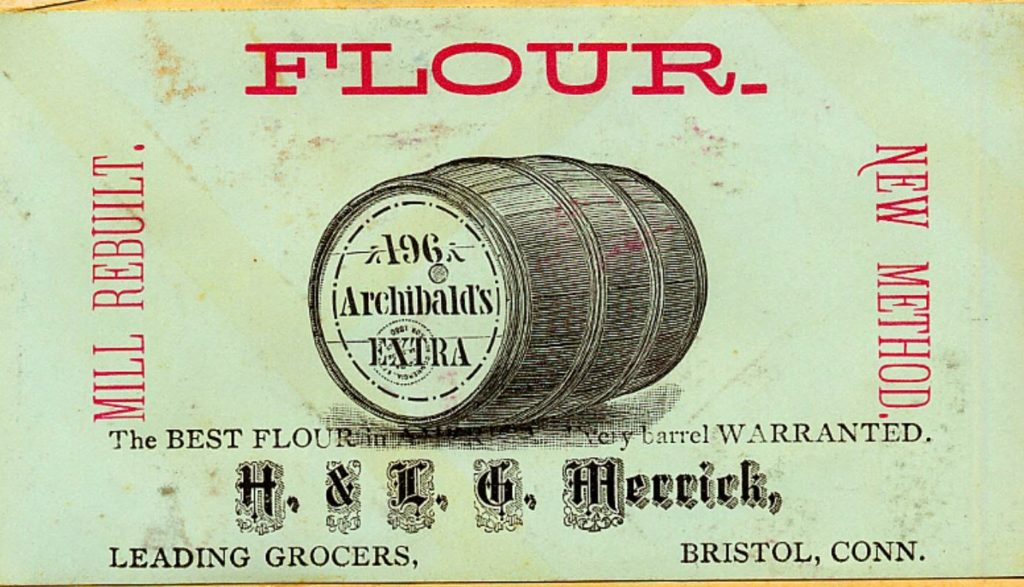

In the meantime, the Archibalds were amassing a reputation for being the best of the best in the milling business. Minneapolis millers would frequently make the trip to Dundas to look at the Archibald mill and inquire about innovations Edward was constantly trying out to improve production and quality. The Dundas Straight flour produced by the mill was consistently recognized as one of the best in the United States, easily collecting $1.00 more per barrel in the east coast markets over any other flour produced in Minnesota.

In 1870, construction on the second mill began. The new mill was four stories with a stone basement laid on the bedrock of the river. A turbine water wheel improved on the wooden wheels used at the first mill. Inside, four grindstones identical to those across the river increased production but maintained the quality customers came to expect from the Archibald mill.

In 1871, production at the second mill was reconfigured to accommodate a new type of wheat–hard spring wheat. In the 1860s, most of the wheat grown in Minnesota was soft winter wheat. John Archibald saw a need to revolutionize wheat farming in Minnesota and believed the hard spring wheat would thrive in Minnesota’s soil and climate. He imported three barrels of Scottish fife, a hard spring wheat, from Canada and asked Edward to find a way for their mill to produce a higher-quality flour with it.

This wheat was typically difficult for millers in the United States to process because most mills were set up to run their millstones low, cracking the kernels and grinding it to flour in just one step. Using this process with the hard spring wheat caused it to overheat and turn to mash. Edward Archibald tinkered with the process and found that hard spring wheat could produce better quality flour than the soft winter wheat if millstones were set higher and run slower.

This innovative process allowed the middlings of a kernel to become the most valuable part of the product. The first grinding cracked the wheat kernel open, then the gluten-rich middling was separated and cleaned before taking another turn through the grindstone. By only grinding the part of the kernel with the most gluten, the flour gave bread a taller rise and was more nutritious than the typical flour of the time.

To increase productivity and make up for the extra grinding time needed with this process, the four grindstones from the first mill were brought across the river and put to use in the new mill. The Archibalds patented their hard spring wheat flour as Archibald Extra at the end of 1871. By manufacturing it as a regular grade flour, the price of spring wheat rose above that of the winter wheat. Therefore, the market on high-quality spring wheat flour was cornered by the Archibald mill until other mills could acquire enough hard spring wheat and reconfigure their mills to produce it. It should also be noted that Edward Archibald patented the design of several purifiers and separators needed to mill the wheat.

Edward and John expanded their milling empire in 1878 by partnering with C.N. Wilcox to build the Oxford mill on the Little Cannon River near Cannon Falls. In its heyday, the Oxford mill handled more than 400 bushels of wheat per day and employed around 35 men.

It was in 1879 that Edward made the biggest improvement at the mill in Dundas. He proposed switching from millstones to a roller system. To accommodate the switch, a two-story wing was added to the mill and the roller system was installed. Thirty-five sets of rollers, two 48-inch turbines, and a Corliss engine that powered the mill were added and the Archibald mill became one of the first mills in the world to use the roller system in its entirety. This innovation led to an increase in production by cutting the time it took to manufacture the flour, without sacrificing the quality customers came to expect from the Archibald mill. At its peak, the mill was producing 800 barrels per day.

John and George eventually moved to Northfield. Edward followed in 1885, two years after losing his wife and adult son to illness. Although the Archibald mill was a leader in the milling industry for many years, competition picked up with increased interest in innovation at the mills in Minneapolis and points east. On New Years Eve, 1892, both mills burned. The 1857 mill was a total loss and the 1870 mill was badly damaged. The Archibalds decided against rebuilding the mill. They sold the 1870 mill as-is to Palon and Watson, local elevator operators who rebuilt and operated the mill into the twentieth century. Today, partial ruins of the mill are preserved but an understanding of the scale of the Archibald milling operation in Dundas has been lost.