At the turn of the twentieth century, newspapers and magazines touted quack cures and healing cults as a successful and fashionable way to treat conditions that traditional medicine could not cure. Practitioners called themselves doctors, but few had any type of medical training, much less a medical degree. For many years, the fasting cure was one of the more popular fads because of the advertised attachment of wealthy, well-educated people who shared their success with anyone who would listen to them.

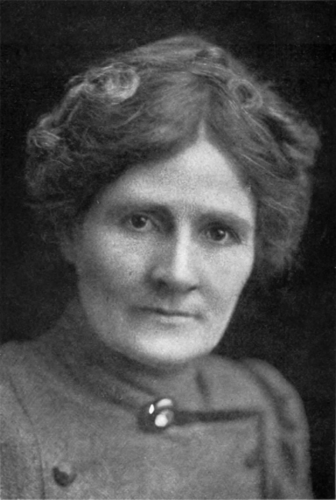

In 1902, Linda Burfield Perry offered therapeutic medical services in Minneapolis, without medical training. Dr. Perry, as she was known to her patients, opened an office downtown and advertised for men and women seeking therapeutic cures for everything from headaches to arthritis. She was a booster for the fasting cure and believed that a person who went without food and only took a small amount of liquid, sometimes in successive treatments, would be cured of whatever ailed them.

Linda Burfield was born in Carver County in 1868 and was the oldest of seven children. At the age of 18, she married Edwin Perry and settled in Fergus Falls. They had two children, Rollin and Nina. The two were estranged after just a few years of marriage. In their divorce papers, Linda claimed that Edwin abandoned her in 1898. Many friends and neighbors believed that her story of abandonment was false, but nonetheless, their divorce was finalized in 1902.

It was at Dr. Perry’s office that Gertrude Young became besotted with the idea of a cure for the partial paralysis that left her arm and one leg slack and nearly useless after a stroke in 1900. The physicians that had been treating Gertrude were only able to address the pain associated with the paralysis but were not able to get her mobility back. Dr. Perry offered her an alternative treatment that she touted as a fix for her mobility problems—a course of 40 days without food and only small amounts of approved liquids, such as half of a cup of tomato broth or strained orange juice when instructed by Dr. Perry.

After the meeting, Gertrude was brimming with hope for the cure promised by Dr. Perry. She was so excited to start the fasting cure that she reported her devotion to the regimen to the Minneapolis Tribune at the beginning of October and promised to report her success to them at the end of her treatment.

Gertrude Young began Dr. Perry’s fasting cure at the beginning of November 1902 in her apartment at 711 Third Avenue South in Minneapolis. A friend stayed with Gertrude while Dr. Perry or one of her hired nurses checked in at the apartment to offer instructions and to check the progress toward a cure.

On November 12, 1902, nearly a month after beginning the fast, Gertrude was found sweating, shaking excessively, and vomiting a thick, dark, foul-smelling substance. Dr. Perry was called. She advised that the windows be opened—despite the cold temperature—to keep the air in the rooms fresh. This only made her worse. Later that day, Gertrude’s friend phoned a nurse for advice on what to do to help Gertrude, whose empty stomach continued to heave. The nurse visited the apartment and after seeing Gertrude’s condition, phoned Dr. Williams—a physician who treated Gertrude before she met Dr. Perry. He recommended that Gertrude break the fast immediately and asked Gertrude’s friend to provide her with bone and vegetable broths and other soft foods until the patient’s stomach could handle more. However, Gertrude insisted that she proceed with the complete 40-day fasting treatment with the lasting hope that she would be cured.

Dr. Williams urged Gertrude to listen to reason. The doctor explained that fasting would never restore the mobility of her arm and leg, and would likely end in her death if continued. Still, Gertrude persisted as her frail body continued to sink in on itself and her skin turned yellow. She died on November 18th—the 39th day of the fast.

As fate would have it, Dr. Williams also served as the Hennepin County Coroner. He opened an inquiry into Gertrude’s death and ordered a post-mortem conducted by physicians at the University of Minnesota. A panel of three physicians concluded that Gertrude died of exhaustion caused by starvation and noted that she had very little blood in her body. Dr. Williams added that Gertrude was healthy enough to climb two flights of stairs to his office without trouble and was “as fat as butter” when he last saw her at his office in September. He judged that Gertrude was the victim of “cruel and unnecessary quackery” and asked that charges be brought against Dr. Perry.

As officials were looking into what charges could be leveled against her, a mystery surrounding the whereabouts of jewelry owned by Gertrude and kept at her apartment whirled around Dr. Perry. She claimed that Gertrude gifted all of her jewelry—including the precious gemstone rings she wore on her fingers every day—to one of the nurses that worked for Dr. Perry. Gertrude’s friend was adamant that she never mentioned gifting anything to a nurse and that her rings were removed and placed with her other jewelry in the bedroom when Gertrude began to lose weight from the fast. The nurse that Dr. Perry claimed to have the jewels could not be found, and reporters and police questioned if a nurse with the name given by Dr. Perry even existed.

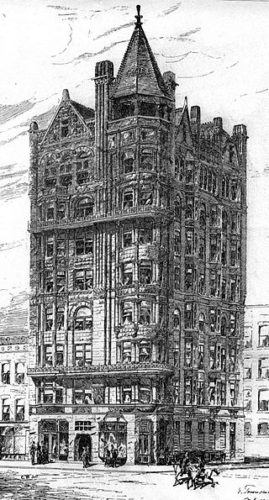

Meanwhile, Dr. Perry called a number of reporters to her new offices in the Globe Building at 20 Fourth Street South in Minneapolis. At the press conference, Perry put on a show of innocence that included a lengthy tirade about medical professionals shunning non-traditional methods of treatment like long-lasting, repetitive fasts as a cure for any disease. She reported that 18 patients had taken the fasting cure under her care and that only one died. She insisted that Gertrude did not follow her treatment instructions closely enough, which resulted in her death. Dr. Perry believed that Gertrude alone was to blame for her death and that the physicians who questioned her methods were merely jealous of her success.

In the end, the panel conducting the inquest into Gertrude’s death found that Dr. Perry could not be charged with any crime. There were no laws that prohibited her methods and authorities reminded the public that Gertrude could have broken her fast and sought the assistance of a physician at any point prior to her death. Many physicians believed that Dr. Perry used the promise of a cure to control her patient for her own gain. They hypothesized that Dr. Perry kept her patients too weak to comprehend that she was taking money and valuables from them as they starved in order to fund her increasingly lavish business.

Gertrude’s jewelry was never found, but shortly after the scrutiny from her death quieted, Dr. Perry moved into a larger office on a higher floor of the Globe Building and continued to practice what she advertised as suggestive therapeutics—including the fasting cure. She married Samuel Hazzard on November 11, 1903, and began practicing her fasting cure under the name Dr. Linda Hazzard. It was during this period that she found herself in the middle of another dramatic event that brought reporters to her door.

It turned out that Samuel Hazzard was already married to another woman in Minneapolis, and his name was actually Samuel Hargrave. The other woman, Viva (Fitchpartick) Hazzard, filed bigamy charges against Samuel in January 1904. Viva claimed that she was Samuel’s second wife. His first wife lived in New York, and Viva believed that marriage had been legally dissolved before they married in 1902. She testified before a grand jury that Samuel deserted her just months after their wedding and that they never divorced. Samuel was charged with bigamy under the name Samuel Hargrave. He pleaded not guilty and bail was set at $3,500. Since he could not come up with the money for his bail, he was held in jail until his February 1 trial date.

Samuel was quite a catch for Dr. Hazzard and she wasn’t about to just let him go. He was completely different from her first husband and the other men she knew growing up in rural Minnesota. Samuel was reported to be over six-feet tall and incredibly handsome with a cosmopolitan flair of modern men. It was said that he could have been a menswear model. His personality was also attractive to Dr. Hazzard; he was a former Army man that exuded confidence and masculinity. Dr. Hazzard believed his appearance and character would lend credibility to her business and would be a beneficial match to her own forceful personality.

As all of Samuel’s legal troubles were being splashed across the pages of the Minneapolis Tribune, Dr. Hazzard stood by the man she believed to be her husband. In fact, she took it upon herself to prove that the charges against him were false and that he was never legally married to Viva. In the days before the trial began, Dr. Hazzard is said to have bullied her way into records rooms across the state desperately looking for proof that Samuel’s marriage to Viva either didn’t happen or that it wasn’t official. Meanwhile, Viva told Samuel that she would be willing to drop the bigamy charge if he would return to their marriage. Samuel stated that his marriage to Dr. Hazzard was all that mattered to him and he was willing to go to prison for their love—if it came to that. His bigamy trial began on schedule.

Throughout the trial, Dr. Hazzard stood by her man. She was in court with Samuel every day, staring down witnesses, audibly admonishing attorneys and the judge when testimony, questioning, and rulings didn’t go their way, and confronting Viva and her supporters outside of the courthouse. When she wasn’t causing trouble in the courtroom, Dr. Hazzard cooed in Samuel’s ear and rubbed his back and shoulders from behind. In the end, Samuel was found guilty and sentenced to two years in jail.

Samuel’s attorney immediately appealed for a new trial and a stay was granted as the appeal worked its way through the courts. Samuel was a free man for several weeks, during which he claimed he was “done with Linda Burfield [Hazzard]” and began making plans for the future with Viva. The appeal went all the way to the Minnesota Supreme Court, but the request for a new trial was denied and Samuel was ordered to report to Stillwater Prison.

Prison life didn’t agree with Samuel. He lost 30 pounds within a couple of months and was ordered to work in the shoe shipping department. He forbid Dr. Hazzard from visiting him and returned his affection to Viva, who was working tirelessly behind the scenes to get his sentence reduced. Viva visited Samuel as often as possible. They talked about their future and began planning life after prison. Samuel’s attorneys managed to legally dissolve all of his previous marriages, leaving him a single man. So, Viva and Samuel agreed to be legally married upon his release. They would then move to Nevada to be near her parents who were willing to provide a home for the couple and a job for Samuel.

But Dr. Hazzard would not let Viva ruin the future she had been planning for so long. She wrote to Samuel every day, asking him to allow her to visit him one last time. After many months, he finally agreed to see her. No one knows what happened during that meeting, but when Samuel was released from Stillwater Prison in October 1905, he walked straight into the arms of Dr. Hazzard while Viva was waiting for him at her boarding house a few blocks away. Dr. Hazzard had won Samuel’s affection and Viva was left shattered.

Their life together was sealed when Dr. Hazzard brought Samuel into her successful medical operation. She anointed herself the owner and fasting specialist at Linda Burfield’s Health Home and Samuel became the manager of the establishment.

Dr. Hazzard had ambitious dreams of opening a grand health sanitorium in the pacific northwest. So, the couple moved to Seattle in 1906. Dr. Hazzard opened offices and advertised her fasting cure in newspapers and magazines that catered to upper-class concerns. She also published Fasting For The Cure Of Disease in 1908 as a way to promote the fasting cure as a treatment for virtually any ailment, including cancer. The book brought in several new patients, many of whom were wealthy, including British heiresses, Dorthea and Claire Williamson.

Dorthea and Claire took the fasting cure with Dr. Hazzard, first in a rented apartment in Seattle, and later at Dr. Hazzard’s makeshift sanitarium in Olalla, Washington. During their time at the sanatorium, Dr. Hazzard forged the wills of both sisters, had herself appointed as their legal guardian due to their supposedly deteriorated mental state, and was named as the sole administrator of their estate valued at over $500,000. She also helped herself to their valuables, wore their clothes, and kept the sisters apart from each other.

After several hellish months, Dorthea is said to have smuggled a telegram to alert her former nanny in England to the situation she and her sister found themselves in. By the time their friend arrived in Olalla to remove the women from Dr. Hazzard’s care, Claire had already died. She weighed less than 50 pounds at the time of her death. Dorothea was too weak to leave on her own—weighing less than 60 pounds. With the help of her former nanny, Dorthea made it to Seattle where she informed the authorities about what was happening at Dr. Hazzard’s sanatorium.

At least 15 deaths were attributed to Dr. Hazzard’s fasting cure in Olalla. The sanatorium garnered the creepy nickname Starvation Heights due to the number of skeletal patients that made their way down the hill and into town looking for food and assistance. Sadly, Dr. Hazzard would only be charged with one of those deaths—Claire Williamson—and even that charge was hard to get. Authorities had to figure out what charges could be brought against Dr. Hazzard, and evidence for those charges needed to be found. But Dr. Hazzard’s inner circle at the sanitorium closed ranks and refused to cooperate with the investigation, making evidence hard to come by. Eventually, a manslaughter charge against the doctor was brought to trial in 1911 and Dorthea’s testimony became the cornerstone of the case.

Similar to the shenanigans displayed during Samuel’s bigamy trial in Minneapolis, each day of the three-week trial in Seattle was marked by spectacular theatrics. Dr. Hazzard was repeatedly admonished by the judge for her brazen coaching and signaling to defense witnesses. One defense witness was accused of trying to bribe a former sanitarium nurse under Dr. Hazzard’s instruction. Then the vice consul’s home was burglarized and Claire Williamson’s trunk of personal papers kept at the home was ransacked.

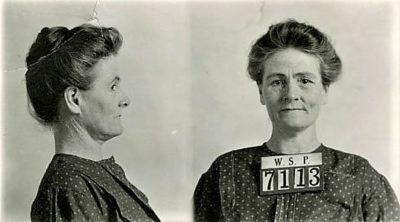

In the end, though, the theatrics didn’t matter. Dr. Hazzard was convicted of manslaughter for the death of Claire Williamson. On February 4, 1912, she was sentenced to the state prison at Walla Walla for between two and twenty years of hard labor. She would serve only two years behind bars.

After a stint in New Zealand where she practiced as a dietitian and osteopath, Dr. Hazzard returned to Olalla in 1920. She opened a new sanitarium, known publicly as a school of health since her medical license had been revoked. She continued to offer the fasting sure to patients until the sanatorium burned to the ground in 1935. It was never rebuilt.

Linda Burfield Hazzard died in 1938 while attempting a fasting cure on herself. Samuel Hazzard died eight years later. Today, local residents still tell stories about what happened at Starvation Heights.

Interested in reading more about Dr. Hazzard’s fasting cure? “The Doctor Who Starved Her Patients to Death” by Bess Lovejoy (Smithsonian Magazine Online) “Olalla’s ‘Starvation Heights’ still causes chills after a century” by Tristian Baurick (Online Article) Starvation Heights by Gregg Olsen (Book)