In the final years of the nineteenth century, Minneapolis was a growing city with an abundance of residents willing to flaunt their expendable income. As a result, a thriving retail industry sprang up to satisfy the desire of the city’s well-heeled citizens to prove that Minneapolis rivaled New York and Chicago when it came to good taste. Much like every other city, the majority of business entrepreneurs in the Twin Cities were men. Minneapolis, however, boasted one of the only female retail entrepreneurs who would help revolutionize the retail industry around the turn of the century.

Elizabeth C. Quinlan possessed a natural business acumen that rivaled most men of her era. She made a name for herself by buying and selling the finest ready-to-wear clothing and accessories in Minneapolis. Her acute business sense and cutting-edge fashion instinct made her hugely successful, while her innovative retailing ideas would be copied by merchants from coast to coast.

Born in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1863, Elizabeth Cecelia Quinlan started working as a sales clerk for Minneapolis’ leading dry goods store, R.S. Goodfellow and Company, at the age of sixteen. Over the next fifteen years, Quinlan would go from earning ten dollars per week to becoming one of the store’s top-earning salespeople.

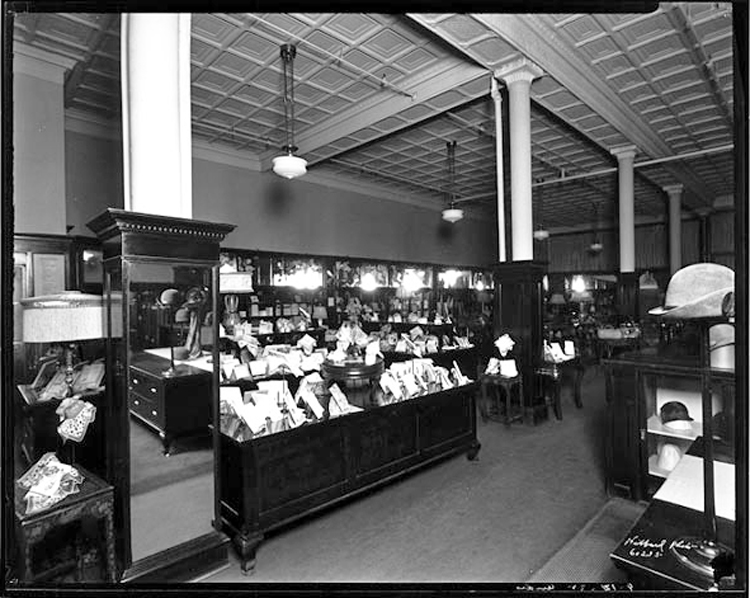

Stores like Goodfellow’s specialized in selling a broad range of merchandise that appealed to the masses. They carried everything from soap and umbrellas to shoes and dresses. Most items of clothing were constructed using tried-and-true cuts and practical fabrics. They sold the items unfinished so buyers could take them to a tailor or seamstress to fit and finish the item or do it themselves. Shoppers could also purchase fabric from a store like Goodfellow’s and have a tailor or seamstress create a wardrobe of custom-made garments. After many years of selling women’s clothing at Goodfellow’s, Quinlan believed a more straightforward way of purchasing women’s clothing could be a successful venture if it were done to a high standard.

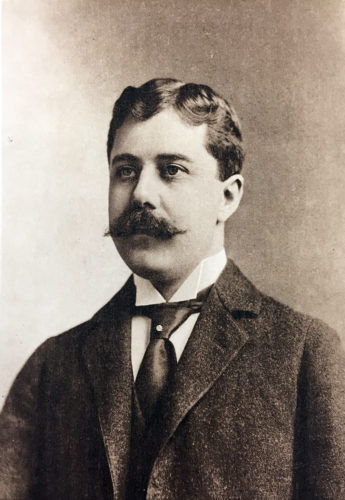

While working at Goodfellow’s, fate dealt Quinlan a life-changing opportunity. Sales department manager Fred. D. Young recognized Quinlan’s talent as a salesperson, and the two became fast friends. They often found themselves discussing the merits of a new type of retail experience–a specialty shop focused on curating a specific kind of merchandise for a particular clientele. In their case, offering high-end clothing and accessories to the women of Minneapolis, all under one roof.

After years of discussing and dissecting the idea, Young proposed that they take the leap and open a shop of their own. Their shop would cater to “clothing the women of the northwest in a manner to make Paris fashionistas sit up and take notice.” It took Young more than a year to raise the $10,000 he needed to open the first shop and nearly as long to convince Quinlan to leave her job to help him run the store.

Their dream became a reality on March 16, 1895, when Fred D. Young and Company opened to a mass of curious women from Minneapolis’ wealthiest families. Located in a back corner of Vrooman’s Glove Company in the Syndicate Arcade on Nicollet Avenue, the little shop could hardly contain the number of customers vying for garments handpicked for the occasion by Quinlan. Young quickly realized that his partner’s savvy fashion sense and intuition for sales was a recipe for success. Even so, when Quinlan approached him about buying six high end, ready-to-wear dresses she found on a buying trip to New York, he was apprehensive. As a burgeoning enterprise, their budget each season was used to procure items the duo knew would suit the ladies of Minneapolis.

Moreover, this bold new idea of Quinlan’s was virtually untested. Only one other retailer in the world had ever tried to sell designer ready-to-wear items, and it went out of business within months. But in the end, Young agreed. Quinlan returned to Minneapolis with a half-dozen brown designer-made wool dresses with a full skirt, taffeta lining, and a high collar that would sell for fifty dollars each.

The brown wool dress proved to be the most popular item on opening day and propelled Fred D. Young and Company into unchartered territory. Within hours, the store sold out of its entire inventory of imported and domestic goods and was forced to close its doors earlier than planned. Quinlan and Young spent the remainder of the day desperately sending messages to fashion houses in Chicago and New York with the hope of replenishing their inventory as soon as possible; cost be damned.

Although Quinlan only agreed to help Young at his store for three months before returning to her position at Goodfellow’s, she realized that this new opportunity was her chance to be a part of a global movement that would change how women’s clothing was sold. She decided to continue working with Young and resigned from her position at Goodfellow’s. While Young managed the store’s day-to-day operations, Quinlan charmed the clientele and sourced beautifully made garments from across the globe. Ladies across the Twin Cities began ditching their made-to-order garb for the off-the-rack apparel at Fred D. Young and Company.

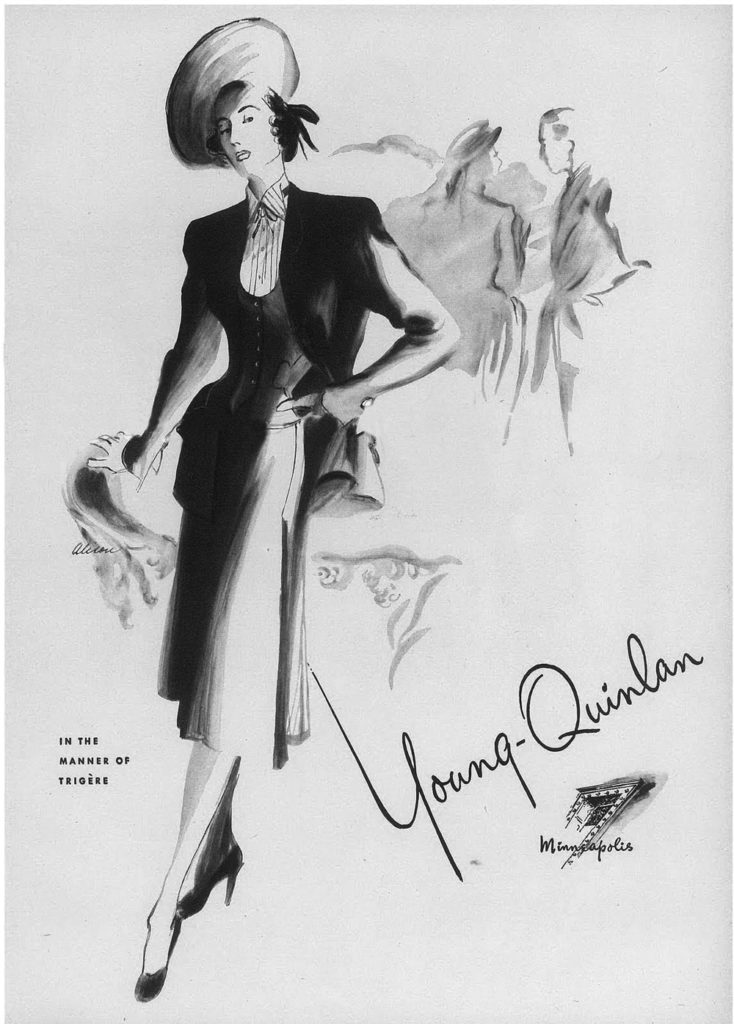

As the prestige of the store grew, so did Quinlan’s unparalleled knack for predicting fashion trends. She continued to make her mark as a buyer in what was affectionately known as the rag trade by traveling to New York and Paris each season on buying trips. After successfully selling all six ready-to-wear dresses on opening day, Quinlan purchased more ready-made designer garments the following season. She discovered a cache of finely made suits with three-inch trains and matching jackets in navy and black for morning wear and pastel colors for afternoon outings. Quinlan purchased a dozen of each style. They were a hit that season, and buyers at stores like Bonwit Teller in New York and Marshall-Fields in Chicago began to notice the blue-eyed “lady-buyer” from the Midwest. Within a year, they were following her lead when making purchasing decisions for their stores.

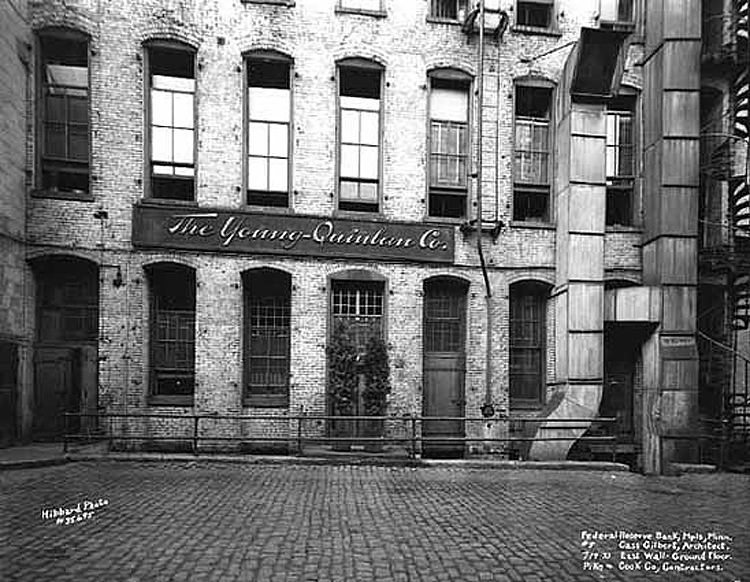

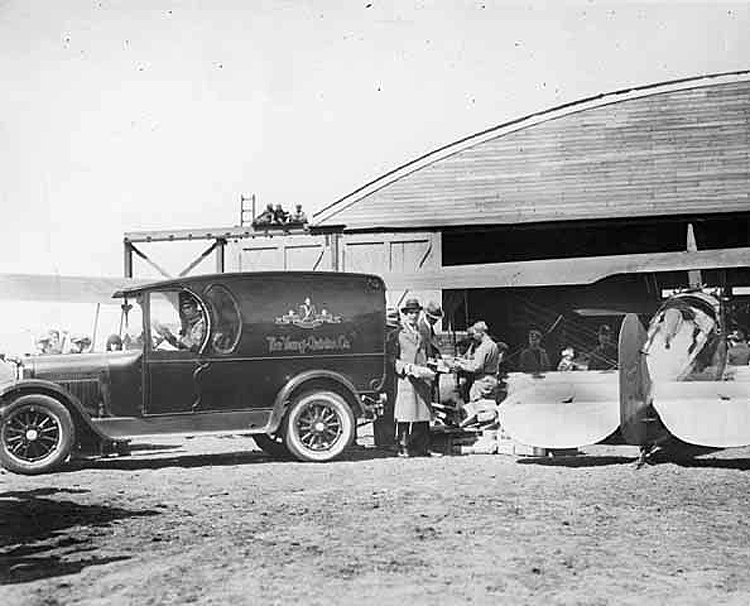

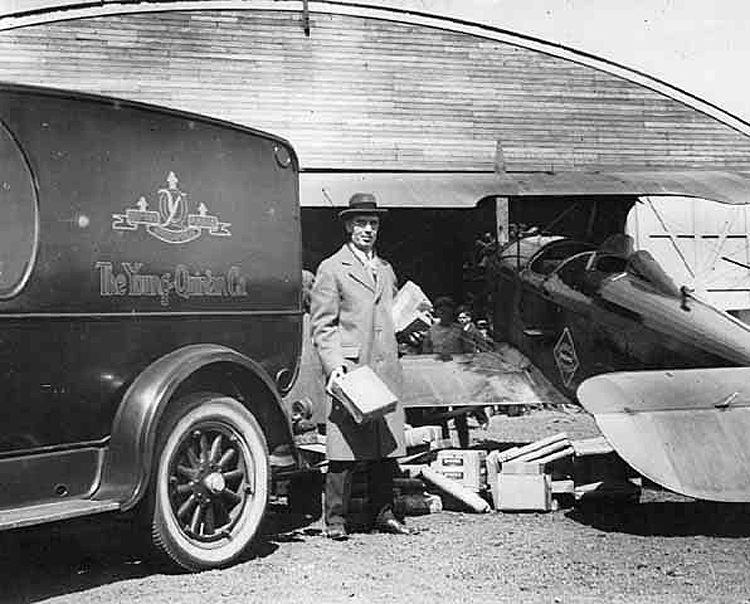

Just as the store began to find its stride in 1903, a fire ravaged the Syndicate Block. The Fred D. Young and Company needed to close for two weeks as repair work was carried out. Just five weeks later, Young was forced to end his day-to-day involvement in the business due to ongoing health complications. As he traveled extensively, seeking treatment for the loss of coordination that plagued him, he left the store in Quinlan’s hands. As a sign of his trust in her ability to carry the store forward, he rebranded the store Young-Quinlan Company before he left.

Quinlan faced the aftermath of a second fire in 1907 that spared the retail space but ruined the majority of the store’s stock. It proved to be a defining moment for Quinlan’s career. With Young away, all of the responsibility of running the store fell on her shoulders. Although her hectic schedule kept her away on buying trips to New York and Europe for months at a time, Quinlan insisted on overseeing every aspect of the store’s management in Young’s absence. She needed time to learn his side of the business as well as keeping up with her own. As a result, Quinlan hired help specifically for tasks she was not familiar with and reluctantly delegated much of the day-to-day work in the store to a handful of devoted staff. Everyone worked tirelessly to ensure that customers never noticed that Young was no longer sharing the duties of running the store.

The success of Young-Quinlan steadily climbed each month. The store expanded its offerings and soon occupied five floors of the Syndicate Block. Meanwhile, the stress of the additional responsibility placed on her shoulders during Young’s illness caused Quinlan to suffer a nervous breakdown. She quietly informed her most trusted employee, nephew William Lahiff, that she was going away indefinitely. Quinlan left Lahiff in charge of the store with the hope that the sunshine and warmth of California would set her back to herself.

While staying at the St. Francis hotel in San Francisco, Quinlan learned of a large fire in Minneapolis. A woman working at the hotel knew that Quinlan lived in Minneapolis and called her room with the news early one morning. Quinlan ignored news from home on her trip and was not much interested until a gut feeling made her call the woman back and ask where the fire was. “The Young-Quinlan store,” the woman replied and followed with the news that the damages were estimated at $250,000. Quinlan rushed back to Minneapolis, prepared to roll up her sleeves and work on rebuilding the store and its inventory, only to find the situation under control.

Although the fire had ruined much of the store’s stock and the building was nearly gutted, Lahiff had already wired manufacturers to rush the delivery of all orders of their spring merchandise. He hastily procured space at a nearby building to reopen the store and mobilized staff to ready the new space for the inventory that would be arriving.

When the store reopened in its new space, the rush of customers wanting to support Quinlan and her staff overwhelmed Nicollet Avenue. Minneapolis police were called in to control the crowd and ensure that the number of people inside the store was manageable. As it turns out, the disaster was good for Quinlan. Her return to Minneapolis was heralded, and she fell back into the familiar rhythm of charming customers and overseeing her store.

As Quinlan found her way back to the store, Young’s rapidly declining health meant that he could never return to the business he loved. He died in his home on December 3, 1911, at the age of 49. After his final affairs were settled, Quinlan borrowed $100,000 to purchase Young’s share of the business from his estate and became the sole owner of the Young-Quinlan Company. Quinlan honored her friend and business partner by never taking his name off the door.

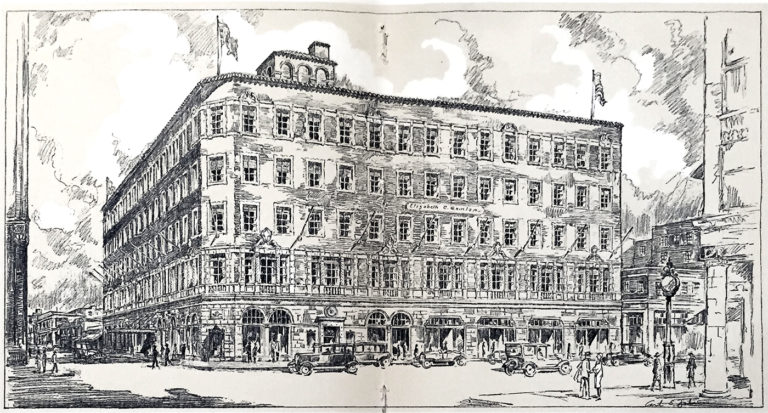

Now under Quinlan’s sole direction, the store continued to evolve. By 1924, Quinlan knew it was time to expand the shop further. Back in 1919, she purchased a plot of land on Ninth Street and Nicollet from George Dayton. The time was finally right to build her dream store on that land. She explained to the Saturday Evening Post her vision for the next phase of the Young-Quinlan Company as follows: “As a merchant, I’ve always tried to take the long view. I’m building for the future. This whole thing is intensely personal with me. My character, my whole philosophy of life, is so tied up with the store, which, after all, is nothing but the outward expression of myself, that it is difficult to separate the two.”

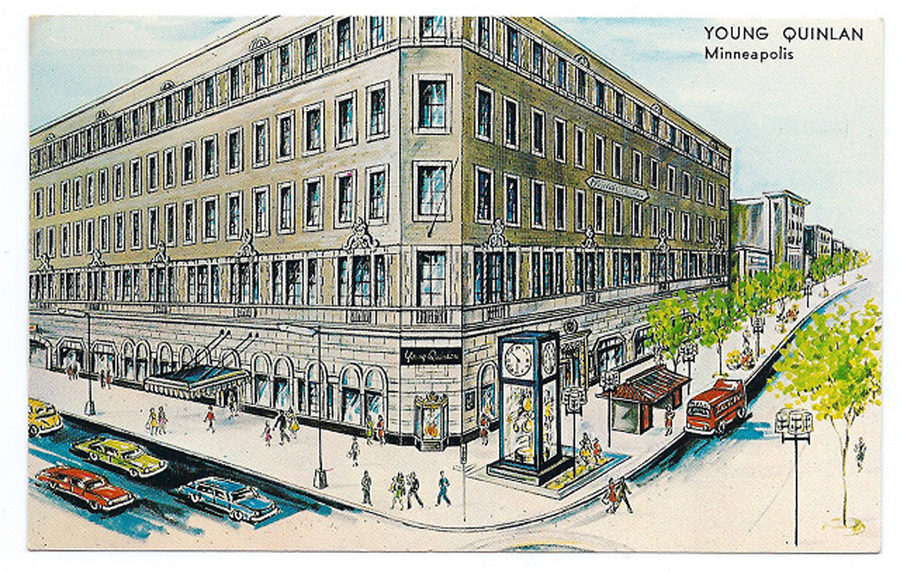

With the long view in mind, she challenged New York architect Frederick Ackerman to design a store for her that felt like a majestic home and was as beautiful as the merchandise it would encapsulate. Out of an abundance of caution, Quinlan made a few requests for her building. First, she wanted a high-tech sprinkler system and fire alarm to offer protection against catastrophic fires that had plagued the Syndicate Block. Next, she asked for the room to grow—the building needed to be engineered for the possibility of adding seven additional floors in the future. Finally, Quinlan requested that the upper floors be easily converted into office space if the store was unsuccessful.

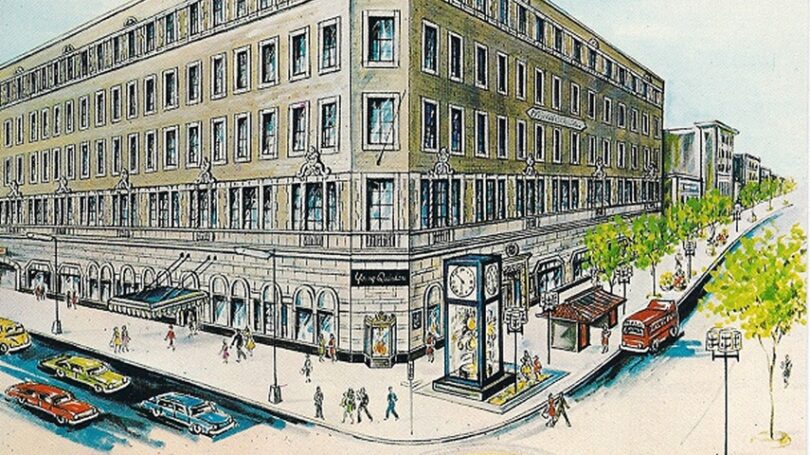

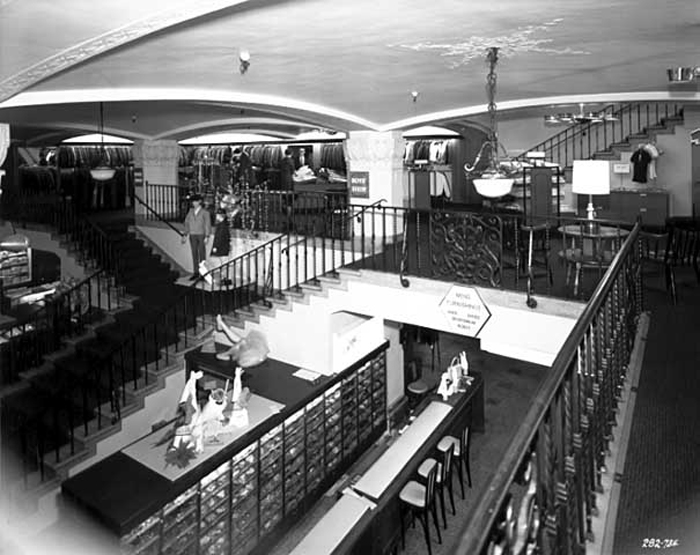

At the cost of $1.5 million, Ackerman produced a five-story masterpiece for the Young-Quinlan Company that was remarkably innovative. It was the first retail store in Minneapolis to feature electric lighting. There was also a 250-stall underground parking garage with an elevator that whisked customers directly to the sales floor. While customers were shopping, their automobiles would be oiled, washed, and warmed for their journey home. Large, brass-framed windows and tall ceilings enabled natural light to flow into the store and allow customers to see the sheen and sparkle of the merchandise. The fur shop featured a remarkable chrome Art Deco ceiling unlike anything seen in the great Northwest. Plenty of lush ladies lounges and a fourth-floor tea room featuring a central fountain made shoppers feel like they were spending the day in Paris.

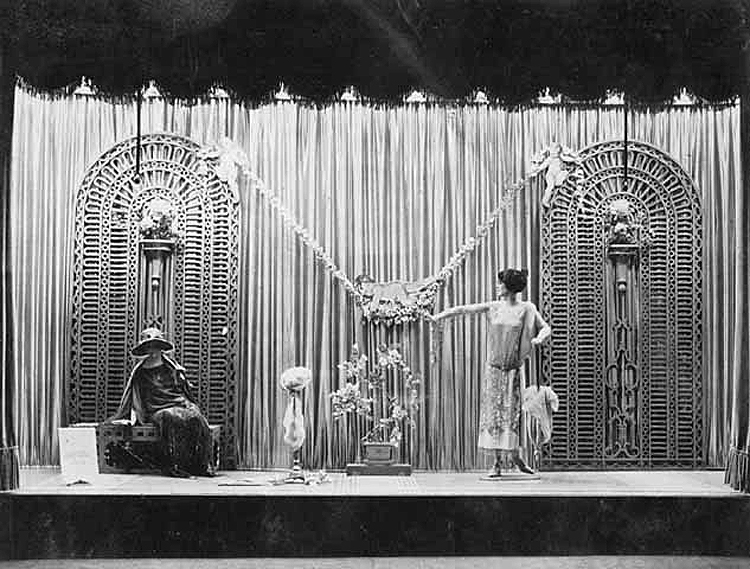

The grand opening of the Young-Quinlan building on Tuesday, June 15, 1926, was dubbed a housewarming by Quinlan. The Sunday before, the Minneapolis Tribune featured advertisements about the formal opening and a special insert devoted entirely to promoting the new building. The insert gave readers a sneak-peek into a grand entry hall culminating in a one-of-a-kind travertine and wrought-iron staircase. The custom-made walnut and brass display cases strategically placed beneath crystal chandeliers on the sales floor. The delicate features in the bathrooms and more. Opening day brought more than 20,000 people to Nicollet Avenue for a glimpse of the grandeur inside the store. The merchandise was all top-drawer—there were no cheap imitations, shoddy materials, or standardized cuts at Young-Quinlan. Shoppers flooded the sales departments hoping to purchase a souvenir to memorialize the day. Handkerchieves, gloves, and perfumes offered exclusively at Young-Quinlan were top sellers that day.

Quinlan loved every inch of her new building. It soon became widely admired and often copied by the top retailers in the country. Shortly after its housewarming, Herbert Marcus of Nieman-Marcus visited the new Young-Quinlan Company building to draw inspiration for a new store in Dallas. Herbert’s son Stanley Marcus wrote in his biography that his father was enamored with the Young-Quinlan shop. After returning to Texas, Stanley tried to convince his father to build the new store in the ultra-contemporary Art Moderne style. Still, Herbert chose to replicate the style of Young-Quinlan instead. Executives from other high-end retailers, including Bonwit Teller in New York and Marshall-Fields in Chicago, also visited the store to garner fresh ideas for their shops.

To complete her new vision for Young-Quinlan, Quinlan wanted a symbol to represent a modern woman’s vibrance, experience, and confidence. She commissioned contemporary Parisian artist Armand Rateau for the job in 1927. The first iteration Rateau presented to Quinlan was a woman lounging with an air of sophistication on a black chaise. The Young-Quinlan Lady was meant to be ageless, and therefore timeless. After analyzing the image, Quinlan became concerned that the woman appeared to be lounging nude. She worried that her conservative clientele might be offended. Rateau reached across his desk to grab a pencil before Quinlan had a chance to reject his offering. He confidently added a string of beads across her shoulders to make it clear that the Young-Quinlan Lady was not nude; she was well dressed. With that, Quinlan agreed that the Young-Quinlan Lady—renamed Inspiration—was a perfect symbol for her store. Since its introduction in 1927, Inspiration appeared on Young-Quinlan letterhead, packaging, labels, advertisements, and on the corner of the Young-Quinlan building facing Nicollet Avenue.

As the 1920s came to a close, Young-Quinlan settled nicely into its new home and its reputation of being second-to-none in upscale retail. The store’s mail-order business was said to have 50,000 customers from all corners of the United States and revenue that reached millions of dollars annually. In addition, famous actresses like Ethel Barrymore and Lynn Fontanne, who Quinlan often mingled with while on buying trips to New York City, frequented the store when they were in town. They were quick to tout Young-Quinlan as THE place for fashionable ladies to shop.

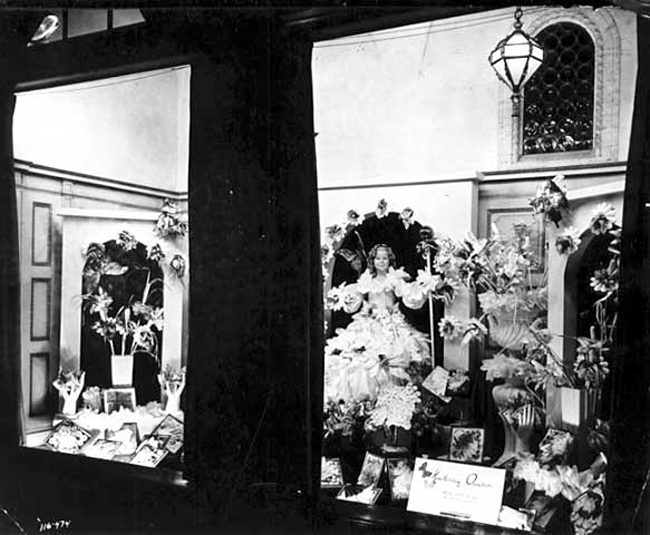

No one could have predicted how the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression would change the retail business. Once the chaos around the news of the crash settled and the reality of a dire economic outlook set in, Quinlan looked to her top executives for ideas to preserve the business and keep employees working. The displays in Young-Quinlan’s fifth-floor auditorium that once brought tourists from around the Midwest into the store were used to lift the spirits of people closer to home.

Each year, crowds of people would flock to see flower shows, Christmas displays, and seasonal fashion shows. In 1932, she brought a collection of rare imperial treasures from Russia to display. In the 1940s, Quinlan presented a couture Hattie Carnegie gown encrusted with 40,000 pearls with a price tag of $150,000. While some visitors would browse the sales floors afterward or stop at the French-themed tea room for nibbles, others would just head home thankful for the distraction.

Young-Quinlan made it through the 1930s by offering moderately-priced clothing and accessories that likely wouldn’t have been offered to customers a decade earlier. Although the items still met the high Young-Quinlan standard of quality, they were simpler and less fussy. End-of-season discounts and (gasp!) sales were used to create new revenue streams and keep the fancy brass doors open. And it worked. Quinlan’s savvy business sense kept the store’s staff—primarily women—working and providing for their families while their husbands were out of work.

Young-Quinlan took the lessons learned from the 1930s into the war years. Yet again, the store provided stable employment for women and a place for shoppers to forget about their worries for a moment or two. But by the end of the war, Quinlan realized she could no longer keep up with the physical demands of running the store. Although Lahiff became vice president and had taken the lead on most of the business decades earlier, Quinlan continued her buying trips to New York and abroad. In an age before transatlantic flights, she told friends that she’d traveled across the Atlantic sixty-nine times.

Quinlan, along with most of her family and loyal staff, were at or beyond retirement age, so she decided it was time to sell her beloved business. She called her old friend Herbert Marcus of Nieman-Marcus in 1945 to inquire about their interest in purchasing Young-Quinlan, but they passed on the deal. Like so many other luxury retailers, Nieman-Marcus struggled through the previous 15 years. They weren’t in a position to acquire another store, much less one so far from their flagship in Dallas.

After 51 years in control, Quinlan sold her beloved store to Henry C. Lytton and Company of Chicago in May 1945. She retained ownership of her building and leased it back to Lytton for $100,000 per year. Lahiff stayed on as vice president and general manager of the store.

On September 15, 1947, Quinlan died from a heart disease that plagued her for most of her adult life. Many downtown retailers took out ads in the newspaper to honor her work in the industry and the community. Some said that retail business came to a halt on September 18 because so many business leaders attended her funeral at the Basilica of St Mary.

Young-Quinlan changed hands several times but never saw the financial success or quality of products it had under Quinlan’s control. The Young-Quinlan building was sold to an insurance company after Quinlan’s death, and Lahiff retired from the Young-Quinlan Company.

Finally, on February 1, 1949, Young-Quinlan merged with Maurice L. Rothschild Company—another Minneapolis retailer. Rothschild and Quinlan had been friendly business associates, often vying for the same products in New York to bring back to their Minneapolis stores. So it seemed somewhat fitting that Rothschild took over the business and operated the store under the name Young-Quinlan Rothschild. The Young-Quinlan name elevated the Rothschild brand to compete with Dayton’s, Donaldson’s, and Golden Rule in St. Paul. But without Quinlan, Young, or Lahiff to steer the ship, Young-Quinlan was just a name. The heart and soul of the once-luxurious store were gone. Young-Quinlan Rothschild finally sputtered to a close on April 30, 1985.

Quinlan’s legacy is quietly evident all around the Twin Cities. The Elizabeth C. Quinlan Foundation has granted millions of dollars to higher education, social service, and arts organizations since the 1950s. But it’s her lovely building at the corner of Ninth and Nicollet that stands in constant tribute to her remarkable success. Many credit Quinlan for planting the seed that would grow into Nicollet Mall. Thankfully, the Young-Quinlan building was saved from Minneapolis’ over-zealous wrecking ball in 1985 by Robert and Sue Greenberg. They pumped millions of dollars into the restoration, reserving space for retail on the opulent first-level and converting the upper floors into offices. Just as Quinlan had planned for decades earlier.

When she was hailed by Fortune Magazine as the foremost women’s specialty executive and among the top sixteen businesswomen in the country, Quinlan responded by saying, “I never wanted to be a businesswoman. I was simply a woman in business.”