The Duluth Homestead Project

The Duluth Homestead Project, also known as the Jackson Project, began under the United States Resettlement Administration (USRA) in 1936. The purpose of the program was to relieve the shortage of sustainably affordable housing for families in Duluth. Qualified families in the Duluth area could receive a house on five or ten acres of farmland for what a small flat would typically cost in town. So, the USRA acquired 1,220 acres of land in present-day Hermantown for the project.

The USRA received more than 350 applications for the 84 homesteads available in Duluth. The qualification process for homesteaders was often subjective. The interview phase of the process carried a lot of weight with whether or not a family would qualify for the program. It included rating families on their need, personal character, age, number of children, prospects of employment, physical condition, and farming experience. The government also required applicants to not only meet the monthly payments for the homestead but have enough left over to pay for the additional expenses related to the home. Taxes, heat and electric charges, maintenance costs, and transportation expenses to get to and from work were some of the additional expenses taken into account.

At first, the government planned to sell the homesteads based on a rate determined by income. By the time construction began and the application process was moving forward, the plan changed. The government altered the purchase agreements to require that homesteaders rent their home for two years before being offered the option to purchase. This would give people the option of leaving the project after two years if farming didn’t work for their family.

The USRA planned to complete the project in two phases. Construction on the first phase of the homesteads began in June 1936. Around 350 men from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) worked on the project while the Emergency Relief Administration built neighborhood roads.

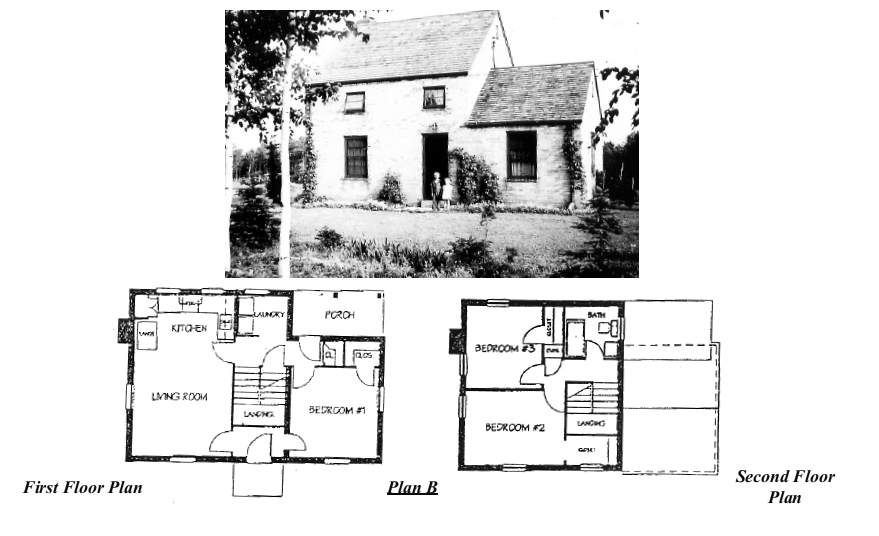

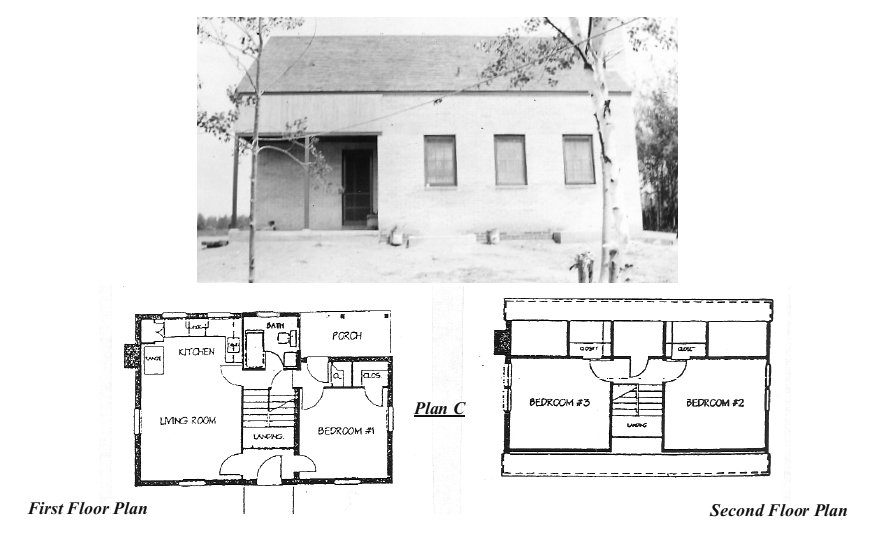

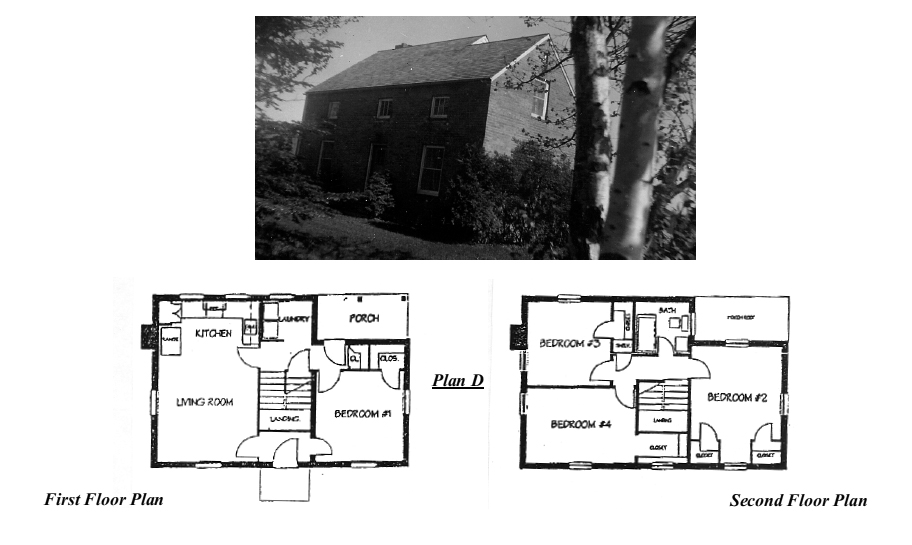

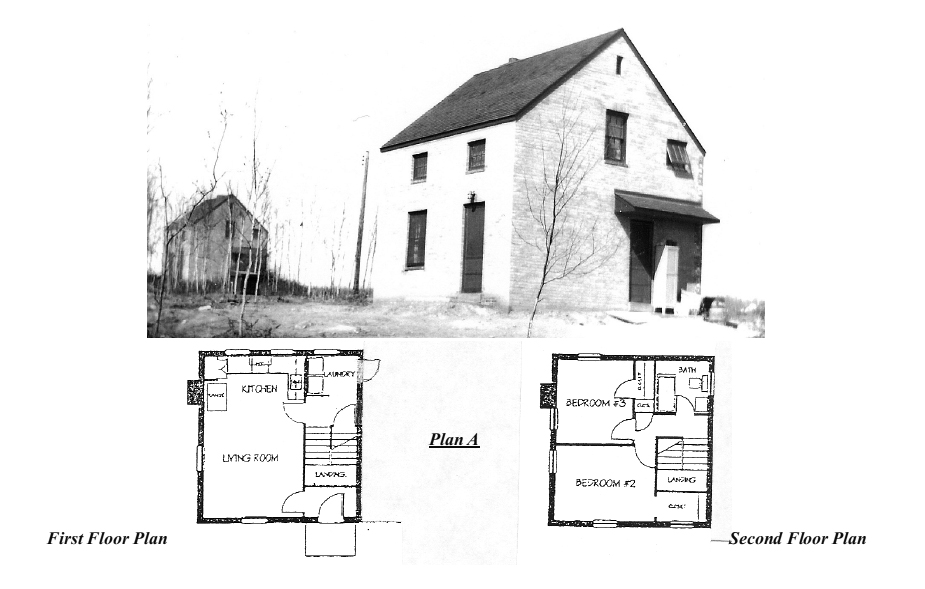

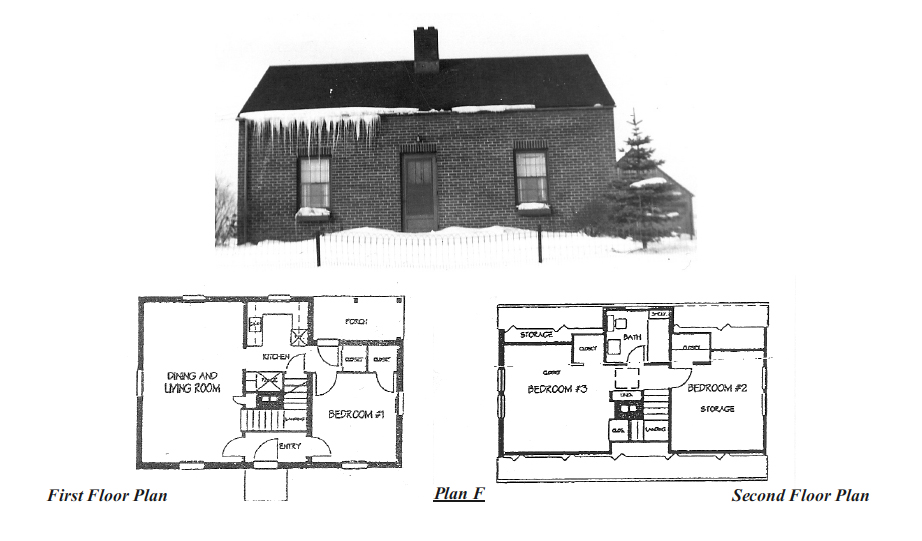

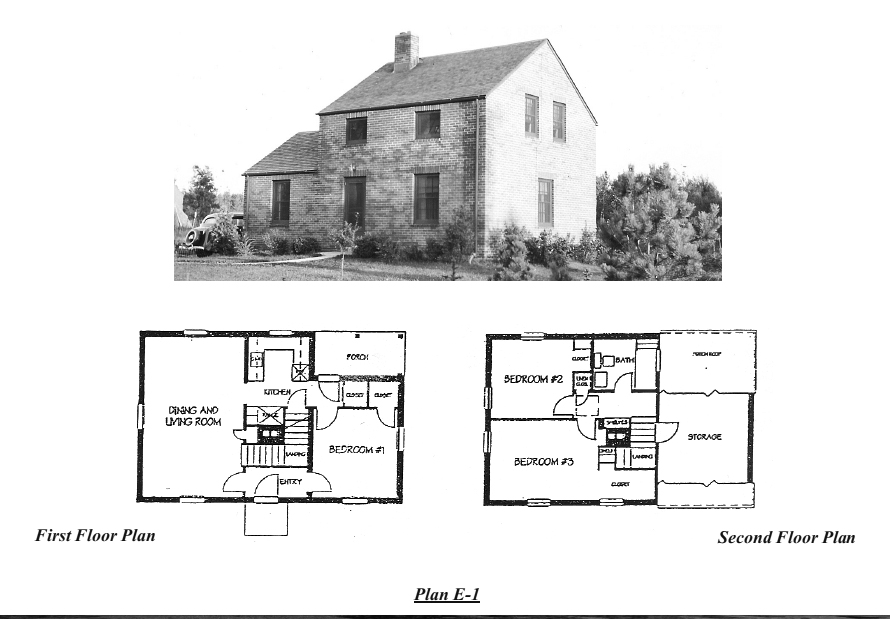

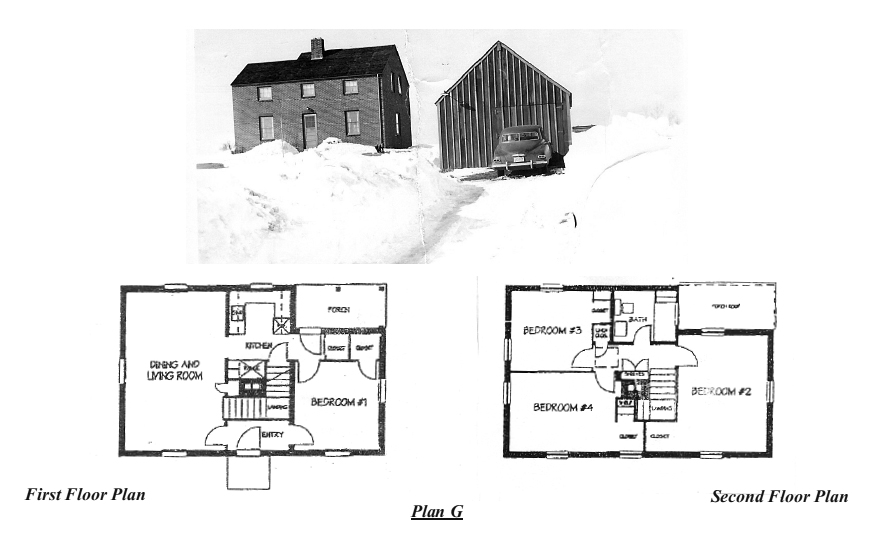

Phase one consisted of 40 homesteads. Four house plans–three, two-level plans and one single-level plan–were approved by the government. All floorplans had virtually the same 20’x30’ footprint, with four, five, or six rooms depending on the layout. Each had a basement foundation and were wood frame covered by red, buff, or pink brick. The kitchen, dining and living rooms were open plan. All of the homes had running water, indoor bathrooms, electricity, individual wells, and were heated by coal furnaces.

The second group of homesteads included 44 homes with a combination garage and barn. Three additional floorplans were available that improved on the original four plans. The houses looked the same from the outside and had many of the same interior features, but were slightly better quality than the first group–each had a separate kitchen, plaster walls, and plenty of space in the basement for cold storage.

The first group of homesteaders began moving into their homes in April 1937, and the second group in November of the same year. By the spring of 1938, all 84 homesteads were occupied. Homesteaders had to provide or purchase all of their own furnishings. The government allocated funds to help the homesteaders who needed assistance with buying furniture by offering to finance items purchased within one year of moving in. Residents did not need to provide a down payment and could negotiate terms of five, 10, or 15 years at three percent interest.

During the first summer, homesteaders typically planted a garden and worked to clear their entire acreage for planting. Families grew common vegetables like carrots, radishes, cucumbers, beets, and potatoes in their gardens. Some added berries, raised chickens, or purchased a dairy cow.

As long as it could provide a sustainable income, what homesteaders did with their acerage was up to them. Most planted crops that would supplement their low wages at part-time shipping or railroad jobs in Duluth. Others got a little more creative. Records show that some homesteaders established berry patches, while others grew hay to sell to other farmers. At least one homesteader launched a small nursery and grew trees, shrubs, and plants on their land.

A school was added to the community in 1938. About 175 first through eighth graders attended the school its first year. High school students were bussed to Proctor High School until six additional classrooms were added to the school in 1941.

A community center opened in 1939 and quickly became a hub for neighborhood activities. There was plenty of meeting space and an auditorium with a 20-foot stage was used for entertainment. The center included bathrooms with showers, and a large, modern kitchen. Weekly meals for the entire community were held here for many years.

In 1939, the Duluth Homestead Association, Inc. was formed. Its membership consisted of families who owned homes built as a part of the Duluth Homesteads Project. Ten years later, the association liquidated its government debt of $225,742. This put the control of the homesteads in the hands of the families that owned them instead of the government.

After the association took control, making changes to the homesteads got a little easier. One of the first changes many homesteaders wanted to make was to move the laundry to the basement. Water and electricity needed to be installed in the basement, but instead of getting government approval before applying locally for permits, homesteaders were only required to have plans approved by the association and permits granted by the city. It took months off of the process. Later, homes were enlarged, remodeled, and improved while maintaining much of their original character thanks to the association.

About 100 similar projects were established throughout the country. However, the Duluth project was among the most enduring and successful of the government subsistence communities. The homesteaders formed a community that found joy in individual success and the accomplishments of the groups as a whole. They banded together to solve problems and worked to make lasting improvements to their community. It grew from a small, government-run farming community into a thriving suburban one.

Duluth Homestead Project homes can be found on Arrowhead Road between Ugstad and Stebner, and along LaVaque, LaVaque Junction, Stebner, and Ugstad Roads